By Sarah Hyder Iqbal

3rd June 2024 | doi.org/10.48060/tghn.130

Knowledge is empowering and transformative. However, the power relations that exist in society influence how knowledge is acknowledged and mainstreamed. This narrative case study documents the grassroots organisation South Asia Sanitation Workers and Labour Network (SASLN)'s transformative efforts to integrate marginalised knowledge and perspectives into mainstream research and policy sectors in order to improve the health and well-being of the sanitation worker community.

In democracies like India, grassroots movements and organised advocacy groups play an important role in catalysing inclusive and people-centred decision-making. Often, it's when social groups and issues are pushed to their limits that such movements begin to unfold. One such example is the South Asia Sanitation Workers and Labour Network (SASLN) which emerged as a grassroots organisation in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2021 and is dedicated to promoting and safeguarding the rights and well-being of sanitation workers in India, Nepal, and Bangladesh.

SASLN recognised the need for collective action from the start to address the insurmountable and multifaceted challenges confronting the region's sanitation worker community, which were exacerbated by the pandemic. The organisation's key initiatives so far have included awareness programmes on education, women's rights awareness campaigns, and targeted efforts around significant events such as Labour Day and Ambedkar Jayanti, the birthday of anti-caste social reformer B. R. Ambedkar. Mental health awareness training and monthly health-related activities have also been conducted, along with health checkup camps in villages. But increasingly, SASLN is seeing its role go beyond a hands-on serving of the community. They believe that challenging the status quo and bridging the gaps in mainstream knowledge production is critical to bringing about long-term change for their community.

The historical entrenchment of caste and patriarchy in India's sanitation sector has significantly shaped the current situation, in which manual scavenging (cleaning human waste by hand), while illegal, is still widespread and confined to a specific community. The mainstream knowledge and policy frameworks, which are primarily shaped by the perspectives of upper-caste, able-bodied, heterosexual males, fail to adequately address the challenges faced by the sanitation worker community. Recognising and understanding the politics of sanitation work, as well as the lived realities of these workers and the complexities of their work, is critical for developing effective policies and scientific solutions in this sector. Such an understanding is currently lacking.

“We, sanitation workers and those from the Balmiki community, feel that many researchers and scientists are ignoring us and our health issues. We have seen a lot of innovations in other areas, such as washing machines, mixers, and spaceships to Mars, but our work has been exactly the same for many centuries. Similarly, technology in health and medicine has increased the longevity of other community members at a much faster pace than ours. Why have we been left out?”

Therefore, to engage more effectively with mainstream knowledge and policy ecosystems, the SASLN team has organised and participated in various brainstorming workshops. In these, they have collectively explored the failures of existing legislation and governmental schemes due to societal, political, and administrative challenges, and together with science and health experts, they have discussed solutions, including safety equipment provision, fair wages, waste management, technology implementation, and health insurance. These knowledge exchange and learning sessions have laid the groundwork for SASLN's ongoing dialogue with the research and healthcare communities to catalyse scientific and social solutions informed by community knowledge and perspectives.

From margins to mainstream

Having come to recognize their role as important ‘connectors’ between the sanitation worker community and mainstream health and research communities, SASLN members also participated in and enriched the discussions on knowledge exchange and community engagement in health research by sharing their unique perspectives. For example, at a workshop organised as part of the Wellcome-funded ‘Centres for Exchange’ project, which included health researchers, social scientists, and activists, SASLN members proposed the concept of 'researchers on hire.' In this model, if a community identifies a question or issue of critical relevance to their health and well-being, they should have the means to readily engage and hire researchers who possess the requisite knowledge and skills to address the specific challenge at hand. This approach embodies a more democratised and community-centred vision of research, where research objectives are guided by the priorities and needs of the community itself. By enabling communities to hire researchers, this model of knowledge exchange fosters a sense of ownership over the research process and outcomes.

At the same workshop, the SASLN team also introduced the ‘Blanket Analogy’ to indicate a shared space for collaboration, inclusivity, and the co-creation of people-centric solutions. The genesis of this analogy traces to when SASLN members would go to various rural or urban localities carrying a blanket on which to sit down and discuss the philosophy of social reformer Ambedkarand other Dalit leaders. This simple yet powerful act of spreading a blanket and gathering for dialogue is what the SASLN team seeks to capture in the 'Blanket Analogy'—a shared platform fostering open communication, mutual understanding, and the co-creation of knowledge that resonates with the experiences and aspirations of the community.

Taking on the reins of knowledge production

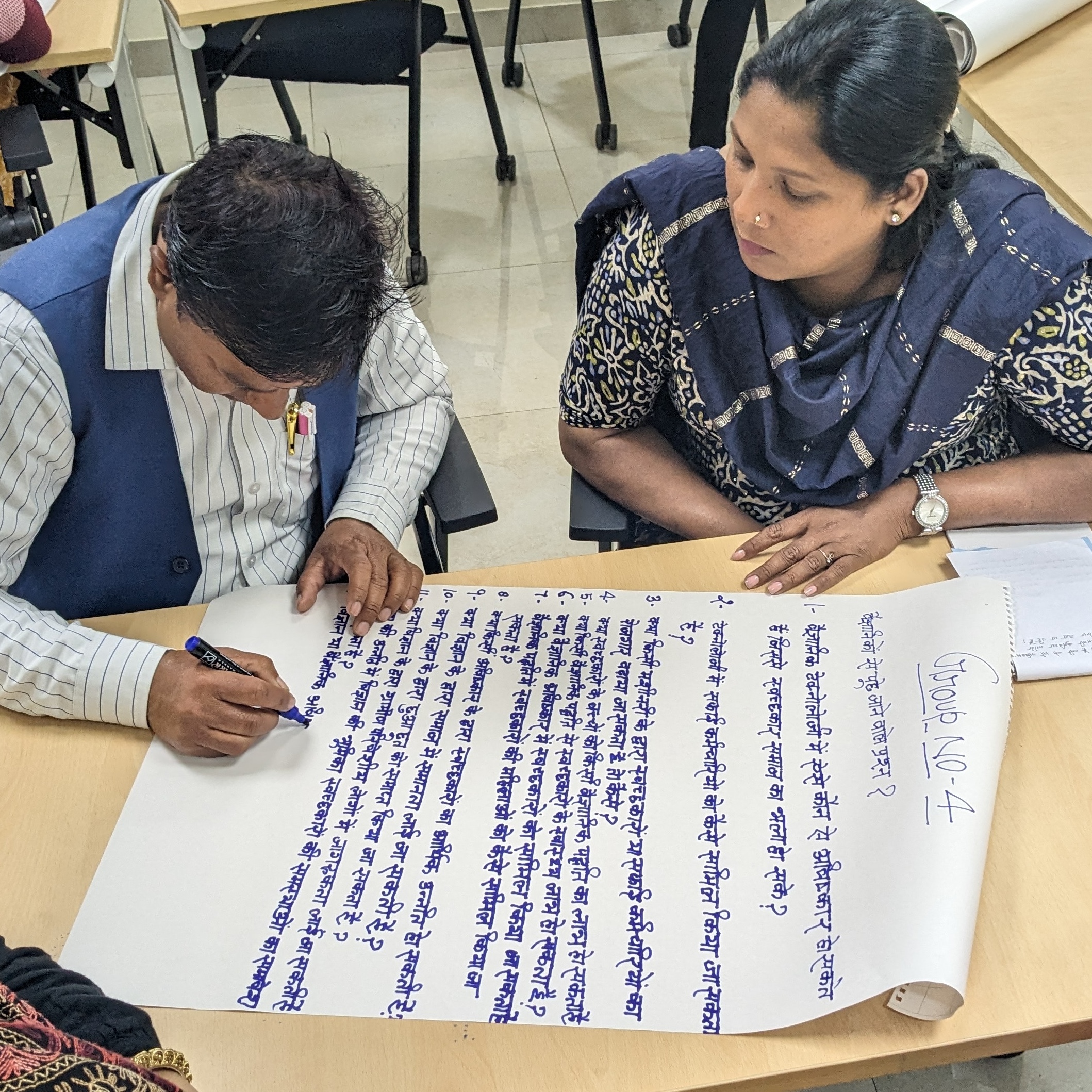

Building on these deliberations, SASLN organised a workshop in collaboration with the Praxis Institute of Participatory Practices for its members to discuss the creation of a ‘Think and Act Tank’, which would aim to produce and mainstream knowledge around sanitation worker health and advocate for improved health policies for all. After all, why should ‘thinking’ be left to mainstream knowledge bodies and ‘doing’ to grassroots community organisations?

The discussions at this session covered various aspects of SASLN's work, including community awareness, skill-building, research, advocacy with the government and private sectors, sensitising external stakeholders, and challenging societal norms.

The members also identified the principles that should underpin the SASLN ‘Think and Act Tank’. They discussed the importance of understanding the ‘thinking process’ and how it occurs, as well as recognising that knowledge-production is political and is embroiled in caste issues that must be addressed. Continuing with this, the group discussed what the ‘Think and Act Tank’ should be, who it works for, and next steps. SASLN and partners also discussed the need for researchers, scientists, and health communities to be better informed about the lived realities and aspirations of sanitation workers so that they can address challenges faced by sanitation workers more effectively through research and policy.

As a next step, and perhaps the first one of the SASLN ‘Think and Act Tank’, a pilot qualitative study on sanitation workers' health was planned to better understand their health status, living and work conditions, and their expectations from science and health communities. A questionnaire was developed after discussion with health and behavioural science researchers, doctors, and other public health experts. This questionnaire was used to conduct interviews with 10 sanitation workers each in the Indian states of Delhi and Uttar Pradesh.

Dismantling hierarchies to promote knowledge exchange

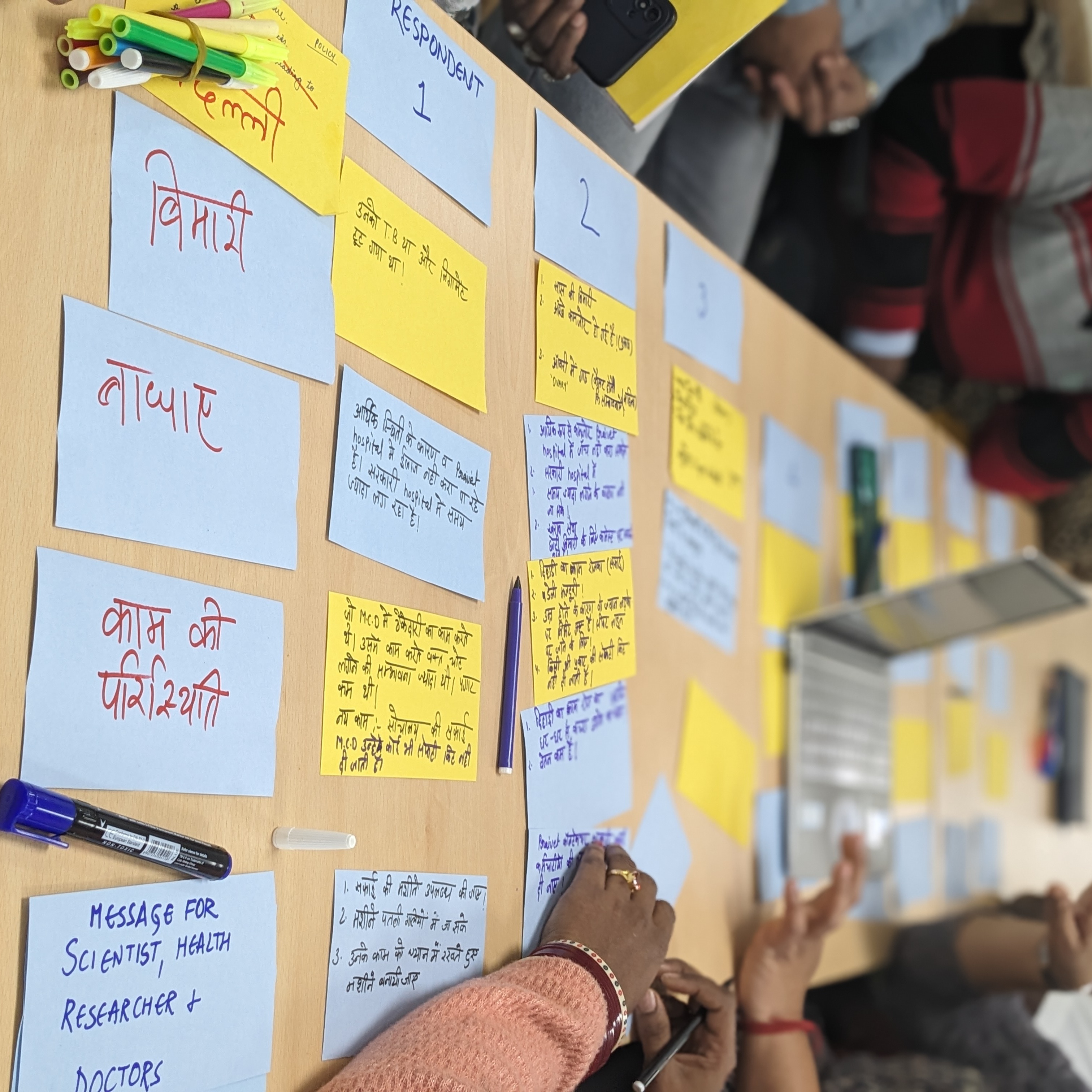

Following the completion of the study, SASLN members participated in a two-day workshop culminating in a public event in commemoration of India’s National Science Day (February 28, 2024). ‘A Peep into Science from the Margins: The Lens of Sanitation Workers’ was attended by researchers, innovators, healthcare professionals, activists, NGO workers, and academics. The workshop enabled the SASLN team to better understand and discuss gender and caste dynamics in science and technology, particularly focusing on unequal access to technology and scientific outputs among sanitation workers. Through discussions and a role-play exercise, participants discussed the accountability of scientists for the welfare of sanitation workers and the public at large.

SASLN members also posed difficult questions to scientists, researchers, and the medical community about the lack of scientific and technological innovations to prevent the risks entailed in sanitation work, particularly manual scavenging, as well as medical doctors' current lack of understanding of social and economic contexts that impact healthcare delivery.

“In the present times, despite technology being so advanced, why are people from the sanitation community dying in sewers?”

Additionally, the concept of a ‘knowledge exchange platform’ was proposed to facilitate dialogue and collaboration in this domain. The proposed platform is envisioned to be owned by SASLN, enabling members to shape discussions and set the agenda with active participation from scientific and health experts. This platform aims to facilitate a better understanding of the sanitation work landscape and its associated politics, enhancing the understanding of all those involved.

However, one of the key challenges of this platform lies in understanding what researchers, scientists, and medical practitioners stand to gain from participating in it or the factors enabling them to participate. Also, SASLN's platform may present research and solutions that might already being undertaken by organisations and innovation hubs. Therefore, it is essential to recognise that the platform may not necessarily produce entirely new knowledge, but rather mainstream insights from the margins. The distinctive expertise and perspectives offered by the sanitation worker community stemming from their lived experiences would be invaluable for research and innovation. Another challenge for the envisioned platform is a lack of funding to enable this production and sharing of marginalised knowledge. Even prior to this, of course, lack of funding has been one of the key reasons marginalized knowledge fails to trigger policy shifts and investments.

Seeding change through dialogue and collaboration

One major takeaway from SASLN’s first knowledge exchange event on National Science Day was the importance of fostering direct dialogue between sanitation workers and scientists, researchers, and the medical community—a practice that is currently uncommon due to knowledge hierarchies. To enable this dialogue, the scientific and medical communities would need to find a common language and commit to shared problem-solving with the sanitation worker community. It was also noted that current mainstream efforts in the sanitation domain lacked a nuanced understanding of sanitation workers' health and socio-economic conditions, particularly from the perspectives of gender and caste.

One major takeaway from SASLN’s first knowledge exchange event on National Science Day was the importance of fostering direct dialogue between sanitation workers and scientists, researchers, and the medical community—a practice that is currently uncommon due to knowledge hierarchies. To enable this dialogue, the scientific and medical communities would need to find a common language and commit to shared problem-solving with the sanitation worker community. It was also noted that current mainstream efforts in the sanitation domain lacked a nuanced understanding of sanitation workers' health and socio-economic conditions, particularly from the perspectives of gender and caste.

It was also acknowledged that although various scientific solutions exist, they are often inaccessible to the sanitation worker community. For example, while an NGO's presentation on antimicrobial cloth and sanitary pads at the event was praised for its significance, the limited availability of these products on the market remained a concern. Furthermore, it was also acknowledged that innovators were often found to lack a comprehensive understanding of the issues they aim to address. The proposed knowledge exchange platform could address this gap by enabling direct interaction between innovators and scientists with sanitation workers.

Moving forward, SASLN and its partners plan to develop and present a problem statement to collaborate with research and innovation institutions to identify and implement solutions. Additionally, SASLN intends to organise workshops in universities where students can engage with the sanitation community and develop innovations in the sector. Leveraging various digital platforms, including social media and existing knowledge portals, SASLN seeks to share the narratives of sanitation workers and amplify their voices on a wider scale.

SASLN's journey of collectivisation and knowledge exchange so far underscores the need for opportunities and platforms that enable communities to shape and inform research and policy agendas. By prioritising the well-being of sanitation workers and challenging systemic inequalities in policy, research, healthcare, and society at large, SASLN has laid the groundwork for catalysing a more inclusive and sustainable dialogue and action on improving the overall sanitation ecosystem in India. To achieve their mission as a ‘connector’ between research, health, and sanitation worker communities, SASLN would require the collaboration of progressive researchers, technologists, healthcare professionals, funders, and policymakers to work towards a future in which every individual has the right to health and the right to benefit from scientific progress and its applications.

This narrative case study has been written by Sarah Hyder Iqbal, an independent science engagement consultant based in New Delhi, India, with inputs from Joginder Parihar, Jyotsana Naik, Ranbir Kumar Ram, and Anil Balmiki from SASLN and Pradeep Narayanan and Neha Narayanan from Praxis.