Increasingly those working in Community Engagement with Research are turning toward experiences within the field of Community and International Development. The increasing use of terminology around 'Participation' and 'participatory methods' attests for this.

However the term 'participation' can mean very different things to different actors. This is something engagement practitioners need to be cautious of. This paper written by Andrea Cornwall (a leading academic and practitioner in the field of participatory community development) encourages greater specificity and clarity around the term and activities performed under its name. She argues that closer attention needs to be paid to 'who is participating', 'in what' and for 'whose benefit'? Also, too often participation in practice does not align with its justification in theory (of democratisation of knowledge, challenging power and community ownership).

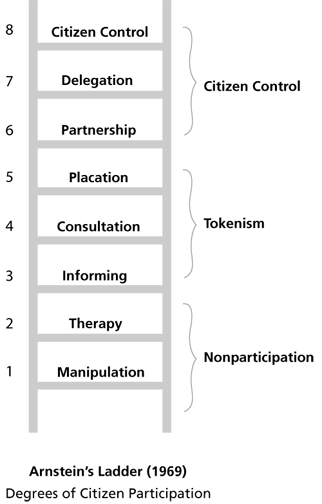

She notes how the term 'consultation' (one of the typologies of participation offered in the classic Ladder of participation mode developed by Arnstein (1969)) is widely used but can easily veil the fact that this can be executed tokenistically as a way of seeking to 'legitimise already-taken decisions'. The paper introduces another 'spectrum' of participation from Pretty (1995) which suggests categories ranging from: Manipulative participation in which 'people's representatives are unelected and wield no decision making power' or 'passive participation’ where people participate by being told what has already been decided or taken place and in which the information shared belongs to external professionals and in which participant voice is unheard to interactive participation in which participants are involved in a joint analysis of a situation and inform action plans (as a right not just a means of achieving project goals) or even self-mobilisation in which people instigate initiatives and develop contacts with organisations to meet their self-initiated goals. In the mid regions are other forms in which participation may take place as a simple exchange of information or resources but in which participants are not part of a process of exploration or learning.

Cornwall also presents a typology offered by Sarah White (1996), which presents some of the interests at stake within various forms of participation to help people think about the varying motivations and agendas behind participation (those of the implementing organisation and those of participants). Whilst these frameworks might read as normative scales from bad participation to good participation Cornwall points out that some of the less in depth forms which are around information sharing can be part of a process that keeps information exchanging and may ultimately lead to more informed community driven action. She also points out that what may seem like the most limited form of participation in terms of transformational potential (such as permitting the participants to choose the colour of a doctor's surgery) might be the start of a longer process of rapport building and handing over of power.

The piece concludes by inviting people who choose to use the term to always ask for specificity around who participates, with what and in which activities? Recognising, as engagement practitioners are aware of, that different kinds of participatory activity lead to different degrees of engagement. She also points out that the political and historical context in which communities are engaged ought to be recognised as fundamental and not to ignore the political and contextual nature of participation and focus too much on its methods.

This work, unless stated otherwise, is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

Please Sign in (or Register) to view further.