Most African governments have committed to transitioning their economies from resource-based to knowledge-based economies. The so-called knowledge economies must guarantee that diversification and value creation is within Africa and benefits Africans/locals. Without question, it calls for more advanced scientific developments that must support this value addition into innovative products and services, but there is just one problem. The ecosystem is fragmented or is almost non-existent. For example, universities still rely heavily on grants from outside Africa with little funding for research and development from central governments despite continued promises. The continent’s ever-intensifying challenges and recently compounded by the Covid 19 pandemic, obliges funding prioritisation to remain focused on other areas of policy than on research and development.

Opportunities to develop a strong and sustainable ecosystem

Amid all these challenges, and the agenda to transition to knowledge-based economies some opportunities present themselves to advance science development. The opportunities lie with developing inclusive and sustainable ecosystems out of project value chains and networks of people and institutions. As an engagement fellow, I had an opportunity to explore how ecosystems form, how networks in cities help form projects and sustain them and how countercultures foster innovation in cities. These opportunities must always be explored from a perspective of inclusion and diversity of people and institutions. The notion of inclusion causes a chain reaction and forces those who concern themselves with solving wicked problems and advancing science and policy to consider how everybody else benefits and is involved. Involving people to solve wicked problems calls for a deeper understanding of those people, their notably their entire social cohesion that is their culture, values, norms, and traditions. Therefore, developing strong and sustainable ecosystems requires an investment into the social cohesion of people and how they benefit from the same ecosystem.

Social cohesion in cities and communities

Every community in every society has their ways that dictate how they relate with one another, how they deal with sickness, situations and materials and objects around them. This is bound by culture, norms, values, and traditions that have been set over a long period of time. All these define the social cohesion of a particular society. Cities and communities get to define their social cohesion based on the level of their reciprocity, the level of “scratch my back I'll scratch yours”. In that way, any new or alien trend or behaviour that is introduced to that community can either confuse or get resistance and requires alignment. Therefore, innovations must always be thought from regional ecosystems perspectives including science development. Sustainable and mutually beneficial ecosystems are incomplete without an investment in the social cohesion. Thus, wicked problems are ecosystemic and must be addressed from the ecosystemic approaches. For example, to overcome health problems, there is a need to consider how a community interacts with one another and how they interact with the medical solutions, or the science being provided. Sometimes brilliant solutions often fail not because of their efficacy but because of where they land, just like in Malawi where some communities of farmers fed Anti Retroviral (ARVs) drugs to chickens to fatten them. To the community, this probably solved a food security problem, not what the scientists imagined. Therefore, the problem here was not in the solution but where the solution lands. A reminder that as we build airplanes, we must also think about investing in the airstrips they land. Science development must therefore consider developing ecosystems that will simply align to existing cultures, norms, values, and traditions thus contributing to the reciprocity that exists. In that way, innovations that emerge will carry the societal norms from which they emerge, with little or no resistance but rather sustained continuity.

Inclusion, diversity and networks in the project value chain

The characteristics of projects as knowledge economy vehicles become clearer as Richard Florida’s theorem of a city as an attractor and retainer of networks. This approach provides the optimum business and intellectual environment for generating and supporting projects since these arise directly from the resources of networks of people and institutions that are inherently combined with the providers of technologies and infrastructure. The nature of projects, small and large, is that they operate in networks and draw on a wide variety of resources, both human and technical in the environment where these networks are concentrated and accessed. If this environment is the city it comes to be treated as an ecosystem supplying projects with business supports of different kinds including financing, marketing and branding, client surveys, retail outlets, export opportunities and training in specialised skills to do with management and technology. These arguments on generating ecosystems out of project value chains and building sustainability were made during my presentation at the 7th Wellcome International Engagement Workshop on Building ecosystems for sustainable engagement projects in 2018 Vietnam.

In this context Florida’s original theorem that argues that cities and their various qualities can be managed and if necessary designed to attract the members of networks and the initiators of projects through their community’s uniqueness, is developed into the aim of managing a number of different city resources into relationships. This further defines the city, its people and institutions as an ecosystem or an enduring cooperating cluster. This informal coalition serves to promote the emergence of some types of projects in a city more easily than in rival cities. Ecosystems have evolved into one of the transactable assets of the city in its aim to attract talent into its networks and initiators of investable projects to these networks.

Unlike conventional approaches of anchoring science development strategies solely on institutions that run in isolation or research centres and universities, this approach challenges city managers, funders, scientists, policymakers, and business leaders to rethink and anchor their strategies and approaches to people-centred projects. Institutions must therefore play a facilitating role within a carefully designed network. Unlike projects, institutions are inherently designed with a sense and some degree of exclusion and that gets to be known as organizational culture. Such cultures can unintentionally be made exclusive by several organisational policies such as human resource policies, procurement policies and many others. For example, when an institution calls for a vacancy, they expect a qualified individual for that position, a filter that from the onset brings a sense of exclusivity. However, projects are more flexible and pragmatic on how communities are involved. Therefore, the so-called project economies or knowledge-based economies demand and call for human-centred approaches to ecosystems. An opportunity not to be missed by those who wish to advance science and build sustainable mutually beneficial ecosystems.

As I was undertaking the Wellcome’s Engagement fellowship, I got to explore how ecosystems form out of project value chains. The engagement was focused on a creative city concept of making the capital city Gaborone as an attractor and retainer of networks, I engaged with various industry stakeholders in Botswana Government, the Private sector and civic bodies. I faced various challenges that are mostly influenced and driven by political alignment, long running and complex organisational cultures, shifting public sector and many others. The culmination of my engagement and research are summarised and illustrated below to demonstrate the above.

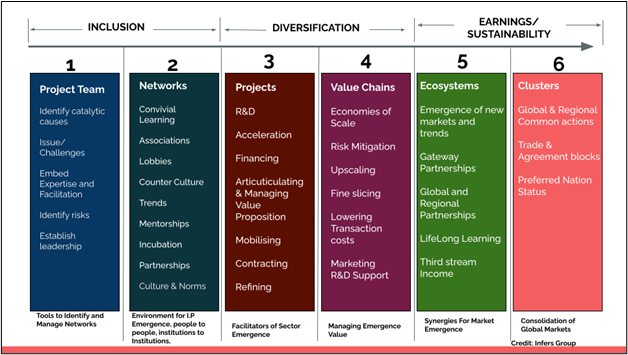

The above diagram illustrates a carefully thought sequence of how an ecosystem can organically emerge from projects. Ecosystems emerge and follow a careful sequence that is informed by emerging issues or challenges, which often begins with teams that are funded or contracted to identify and provide a solution to the issue and its aftereffects. (Diagram 1)

The first stage 1 and 2 are all about organising the right people, expertise, institutions towards a common mission. The project team will identify expertise, risks, leadership to undertake the mission. The same project team will identify a network or emerge from an existing one that surrounds the issue, for example, a network of association/ individuals against climate change or HIV. This is the point where engagement among members of the networks is flexible and can easily be penetrated, an important attribute of inclusion and diversity. The norms that define involvement are often based on reciprocity, common understanding and the identity of networks towards achieving a common goal that benefits those in the network. Self organisation, partnerships and incubation are easily achieved and formed into a project based on the shared cultural norms, values, and shared interests.

Once self organising of people and institutions is achieved, projects in stage 3 will then facilitate and determine the research and development, financing, contracting, acceleration, marketing, branding and value management. If the same process is repeated and several projects are developed with project partnerships that are public, private and civic oriented, it will result in stage 4, where there are value chains that are managed by networks of people and institutions. The same framework of networks of people and institutions will reduce the role that institutions play in managing and implementing projects. The well organised cooperation between people and institutions will as a result create an opportunity to manage future projects thus giving an ecosystemic form. This stage will facilitate economies of scale, risk mitigation, upscaling, lowering of transaction costs, research and development and other crucial components of doing business and value creation.

The management of these networks co-operations will result in project value chains and careful investment in them will lead them to be identified as hubs and centres of excellence that will define an ecosystem in stage 5. Different disciplines and sectors will have various similar project value chains; the relationship between various value chains and hubs can be defined as clusters in stage 6. At this stage, this is where sustainability is ensured because it is the direct connection between the project value chains, hubs, centres of excellence and the market where the return on investment is ensured. This is where policymaking must play a major role to facilitate regional partnerships and Trade agreements.

Being part of an ecosystem simply means that an institution or a professional group undertakes to be responsive to the needs of networks and projects in its city or region. This undertaking includes the expectation and willingness to work alongside other sectors and institutions collaboratively or as a coalition of stakeholders through projects. Effectively ecosystems aim at managing or making available, existing institutions and subsectors to the needs of projects and project participation. The concept of ecosystem, which is often misunderstood as an institutionalization of resources within an encompassing structure, infact free resources to function in a less formal and more ad hoc manner in relation to projects as if the organisations in a city were participants in a network. This creates an opportunity for science development partners to play a role by becoming partners of the ecosystem, opening an opportunity to third stream income. Through this sequence, ecosystems can never be similar and must not be treated as such due to cultural, business and political differences.

Implications for health systems and science advancement

There is little doubt that the managerial philosophy of using cities as catalysts or ecosystems to shape and enhance desirable properties and changes in networks and projects has become the norm with civic management and urban investors. The efficiency of de-corporatising intellectual property creation and innovation based on the value creation process, bypassing the risk of providing growth and continuity onto the network of service providers who are only precariously and temporarily employees is well recognised. Can this system provide increased efficiency and perhaps also great access to opportunity within the health system? The continuity and value created by projects must therefore be retained by facilitating institutions.

While health problems are similar, the way they are responded to must be different. Health systems must not be treated with a one size fits all approach mainly because of the social cohesion that is determined and enforced by the cultural differences found in cities and regions. The organic emergence of ecosystems clearly ensures that how people organise themselves on the ground through projects and to overcome challenges they face will always be through their tacit knowledge. That is the defining moment for sustainable and inclusive ecosystems. The tacit knowledge on reciprocity among communities and institutions must be taken as an asset to invest in, as it is the glue that binds the effectiveness and implementation of any project. An attribute that defines most of Botswana’s policies that are developed and created by foreign consultants and fail on implementation. It has become a common saying in Botswana that they have very good policies but they lack implementation. This is simply because, unlike in their early founding days, most policies are now designed outside their tacit, thus becoming too alien or complex to understand to those who implement. Therefore, social change management must undergo an intensive assessment for those who wish to advance science and improve health systems in partnership with national policy developers. This social management must without doubt position people in the centre to determine health systems, also bringing the private sector and the state together to form Public Private Civic Partnerships (PPCPs).

The above diagram is an attempt at how partnerships between the Public, Private Sector and Communities/ Civic bodies can facilitate the emergence of project value chains towards achieving a sustainable and equitable ecosystem. The co-creation and co-production of the partnerships between public, private and community/civic bodies would ensure projects with shared value. (Diagram 2)

The health system has always been a form of public-private partnership close to a parastatal model. The public sector has created infrastructure and skilled personnel in accordance with state policies and funded these with public revenues or sovereign debt. The private sector involvement is expected to bring efficiencies through competitive market forces supported by necessary and relevant regulations. Communities through their various civic bodies will provide organising, relevance, advocacy, coordination, regulation, participation and other several roles through various projects. This model provides an opportunity to all stakeholders, including communities, science development partners, policymakers and business sectors to create shared value from solving challenges. An ecosystem that facilitates well-coordinated projects, creates an opportunity for science development partners to interact with people progressively and easily on the ground around a specific issue/ challenge, creating value out of that issue/challenge. This approach will facilitate what many scholars identified as the Stakeholder Value model, moving away from the current dominating Shareholder Value Model.

In its early days, Botswana’s approach to development was influenced by people centred with a PPCP form. How the country used to build dams, schools, roads and overcome challenges such as health and drought was always about mobilising people on the ground. For some reasons that are attributed to successful economic growth and the government becoming wealthy, it transitioned the government to turn into a major economic player that distributed and solved challenges alone. To date, the state has turned its public service managers and parastatals into solution providers rather than facilitators. An approach that limits the diversity of ideas and inclusion of people as well as the creativity in policy development. However, as a micro-economy, the country could easily implement the above models illustrated above to create an inclusive, diversified, sustainable and mutually beneficial ecosystem.

Abraham Mamela is CEO and Founder of Infers Group and a Wellcome Engagement Fellow

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

Please Sign in (or Register) to view further.