Community and public engagement (CPE) should, by definition, seek to include as many groups with diverse experiences and realities as possible. However there is currently a lack of representation of certain groups in CPE communities and activities. Which groups are excluded will differ in certain contexts; in the UK, this includes people from ethnic minority backgrounds, people on low incomes or disabled people. A group session at the 2018 Wellcome International Engagement Workshop explored this issue; symbolically, many of these excluded groups were not represented at the workshop, exemplifying how they are often left out of conversations about their inclusion.

One of the speakers leading this session was Patrick Collier. Patrick is an independent arts producer and the executive director of Access All Areas, a UK-based theatre company that make urban, disruptive performance by learning disabled and autistic artists. These theatre and dance projects raise issues that are important to the broader disability rights movement.

A recent project was a collaboration between Graeae Theatre, La Fura Dels Baus, and 100 disabled artists local to Chennai, India. The show played to about 11,000 people in one night, demonstrating the scale of the audience that these types of open-access community-driven projects can reach.

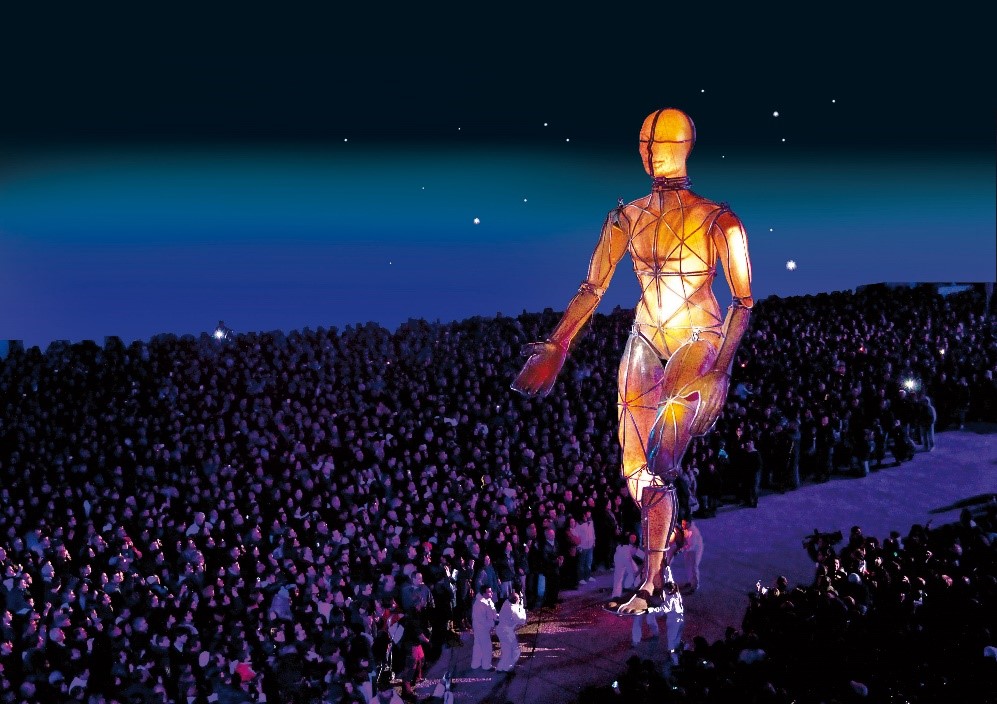

The theatre project in Chennai was fuelled by a social consideration of disabled experience, which looks at the disabling factors of social context, rather than individual impairments. The social model of disability argues that it is social structures that disable people, rather than a perceived “difference” or medical diagnoses. For example, a wheelchair user is usually able to access a space that has ramps, lifts and even floor surfaces. When appropriate accessibility measures are not in place, however, a wheelchair user is disabled. This idea can be extended to people’s attitudes, when social attitudes towards disabled people can often be as disabling as any physical structure. It is therefore the environmental and social factors – often encapsulated in society’s lack of allowance for variety in people’s access needs – that disables people. These conversations within the Chennai project led to the development of skills training workshops with local disabled people and local organisations, culminating in a large-scale production led by D/deaf and disabled artists. The performance involved 24-metre-tall puppets, a chorus of D/deaf dancers, a ‘human net’ operated by wheelchair users with performers suspended 50+ metres in the air, and other high-spectacle elements.

The project was directed by Graeae’s Amit Sharma, who identifies as disabled. Involvement of disabled cast members moved the conversation away from a charity model that often disempowers disabled people by treating them as victims or unable to lead – and sparked debate and questions about the barriers disabled people face in getting involved not just with projects like this, but with other aspects of modern Indian society too. How are the homes they live in – sometimes low-quality shared accommodation such as hostels – adapted to their access needs? Why do buses and other forms of public transport not have disabled access? Difficulties in these areas meant that participants sometimes struggled to get to rehearsals and performances, initiating high-profile public conversations in the media about how these structures could change in Chennai and beyond. The project also focused on the question of how Graeae Theatre and other western practitioners ensure these conversations are led by local people and appropriate specifically for India, and not an imposed version of western ideas around the social model of disability.

Another project Patrick was involved in was MADHOUSE re:exit, a production led by learning disabled and autistic artists from the award-winning performance company Access All Areas. The production reflected on the history of people with learning disabilities being institutionalised – i.e., put into care systems run by the state – and how their treatment by society would often lead to ‘secondary handicaps’, as described before using the social model of disability. The full show was seen by over 2,000 people, but also received a lot of media coverage, and so is estimated to have reached around 1,200,000 people across the UK via national broadcasters and viral digital content. Patrick emphasised the value of working with high-profile theatre- and film-makers to achieve the kind of reach seen by this and the Chennai project, as well as their ability to emotionally engage audiences.

---

The content on this page forms part of the online report for the 2018 International Engagement Workshop “Taking it to the Next Level: How can we generate leadership and develop practice in engagement?". To learn more about the workshop, access the rest of the report and browse the video presentations, discussion summaries, and tools, visit the workshop page.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Please Sign in (or Register) to view further.