This article, by Wilkinson et al. (2017), deconstructs notions of ‘community’, and the ways it is conceptualised and understood, in order to critically reflect upon methods of engaging ‘communities’ during the west African Ebola epidemic in 2014. The article concludes that although the epidemic was brought to an end by changes in transmission-associated practices and collective action, some ‘community engagement’ interventions were not as ‘community’ unifying as is widely reported.

The article begins with a review of academic literatures that endeavour to define ‘community’. It finds that the term is understood differently by different groups and writers, which has lead to a lack of clarity on what actually constitutes a ‘community’. They find that public health practices often reduce ‘communities’ to particular, physical geographies. The article argues that these reductive constructions of ‘community’ are problematic as they bear little resemblance to local experiences and realities. The article suggests that this leads to a number of problematic assumptions and practices:

- Imagining ‘communities’ as static, unchanging and visible (rather than dynamic, ever-changing, and open to context-specific representations)

- Presuming social cohesion and neglecting the array of social divisions and hierarchies

- Overlooking power relations and reinforcing, or creating, social hierarchies

- Assuming ‘one size fits all’

- Systematically excluding marginalised and vulnerable groups

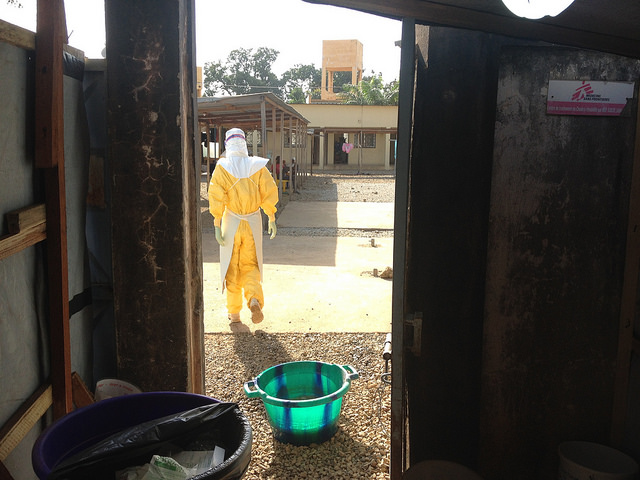

The article reflects on a number of examples of ‘community engagement’ during the Ebola epidemic, including the practices of an international response team in Guéckédou, Guinea. The article compares the response team’s approach to engaging the ‘community’ and identifying ‘community leaders’ (either through self-identification or from their professional, civic or political associations) to that of an anthropologist, Julienne Anoko. Anoko spent a number of days talking to people and asking them who they would trust and nominate to speak on their behalf. The two approaches produced strikingly different results; not a single name was found on both lists. The article uses this example to reveal the consequences of top-down processes and uncritical, externally-generated conceptions of ‘community’ that fail to recognise local realities and experiences.

“The lesson from Ebola, then, is not that ‘communities’ can stop epidemics and build trust; it is that understanding social dynamics is essential to designing robust interventions and should be a priority in public health and emergency planning” (Wilkinson et al. 2017)

Click here to read the full article.

Click here to download the full PDF.

Image: EU Civil Protection and Humanitarian Aid Operations EC/ECHO (CC).

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Please Sign in (or Register) to view further.