There are many different approaches to engaging non-researchers with research. The application of participatory visual methods (PVM) can enable non-researcher participants to work with researchers to actively shape an interactive science engagement process through the co-production and exchange of visual outputs. At the 2018 Wellcome International Engagement Workshop, Gill Black presented Bucket Loads of Health, a recent public engagement project facilitated by the Sustainable Livelihoods Foundation that took an innovative approach to working with PVM.

Image: Gill presenting at the workshop | Minh Tan

In recent years, South Africa has been facing severe challenges with its water supply. In mid-2018, the Western Cape Province was declared a drought disaster zone and its residents were subjected to unprecedented water restrictions. Saving and reusing water - already common place in some parts of the country - became much more widely practiced, making the associated health risks ever more pressing. The Bucketloads of Health project was implemented during the height of the water crisis. It aimed to bring non-researcher participants into a research engagement process with a team of water microbiologists at Stellenbosch University (SUN).

The SUN microbiology team, led by Professor Wesaal Khan, explore strategies for the treatment of rainwater that has been harvested from shack roofs in informal settlements. The goal of their research is to make the harvested rainwater safe for domestic use, and ultimately for drinking. Enkanini – an informal settlement just outside Stellenbosch - is the current setting for Professor Khan’s research. Gill approached Wesaal and her team in 2017, to find out if they would be interested in engaging members of the Enkanini community in their microbiology research. They were delighted to have been asked and did not hesitate to take up the opportunity.

The scope and scale of the Bucketloads of Health project was expanded by including a group of residents from Delft, a formal settlement in the northern suburbs of Cape Town. The settings of Enkanini and Delft vary significantly in water accessibility. Households in Enkanini have no running water. Residents of the informal settlement collect water from communal standpipes. As such they live with a perpetual water crisis. The majority of households in Delft do have access to running water, but this area of Cape Town was particularly hard hit by the enforced municipal water restrictions.

As part of the Bucketloads of Health project, the SLF team held creative workshops with residents from both participating communities. During these workshops, participants shared their varied experiences of living with water shortage through art, music and narrative storytelling.

Bodymapping

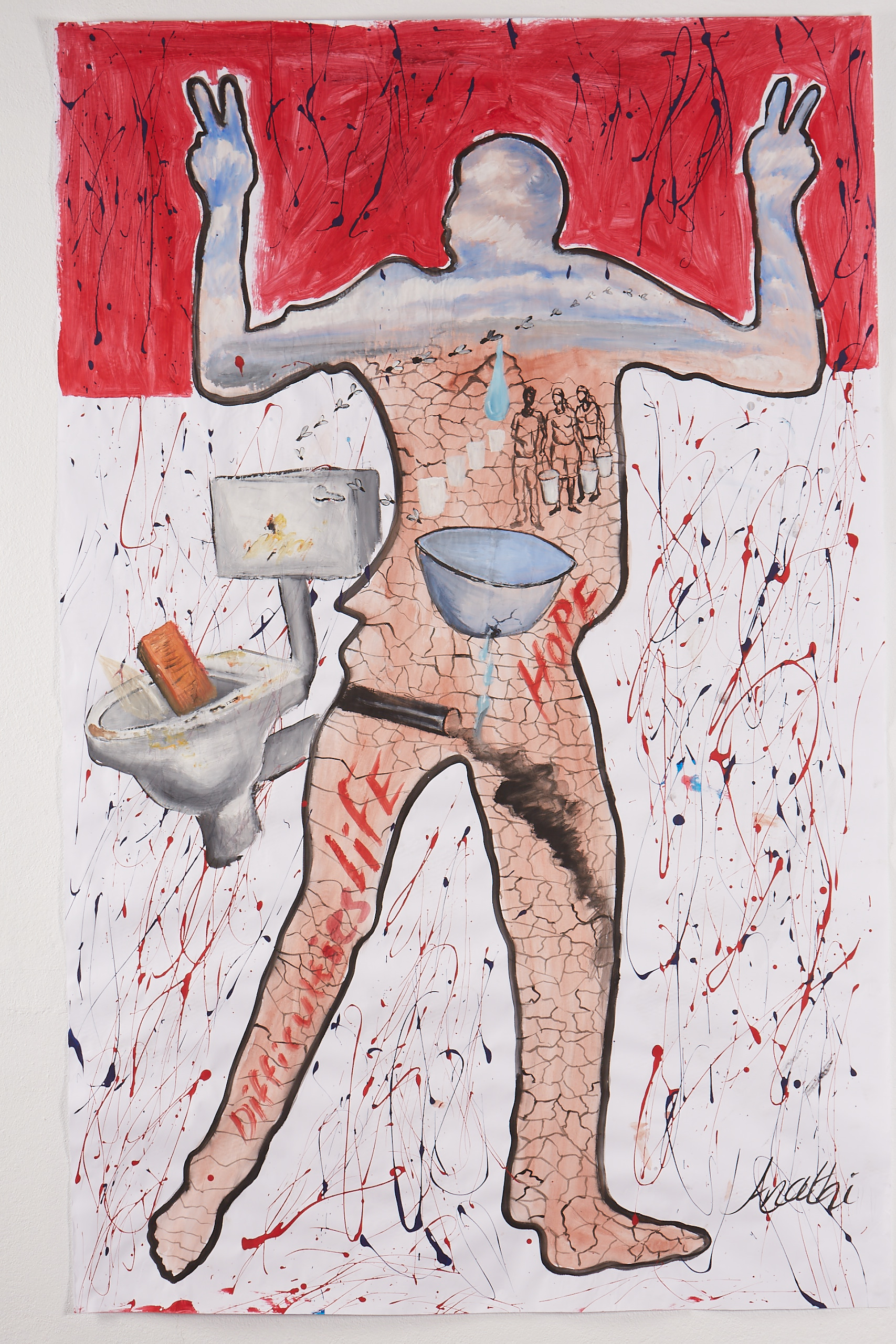

One of the arts-based activities involved the participatory visual method of body mapping. All of the Enkanini (12) and Delft (15) participants created individual, life-sized body maps that captured their embodied experiences of living with water shortage, and their relationships to water in and around their homes.

Knowledge exchange workshops provided the community members with an opportunity to present their body maps to the microbiology team. They used their body maps as platforms for storytelling, giving detailed descriptions about the multiple ways that restricted access to water was affecting their health and wellbeing.

Image: An example of a bodymap created in Bucketloads of Health | Sustainable Livelihoods Foundation

During the knowledge exchange workshops, while they were presenting and discussing their research with the Enkanini and Delft participants, the scientists referred to what they had noticed in the body maps. As part of the discussions, the Enkanini participants strongly expressed their opinions about the multiple research projects that had been done in their community over the past few years. The scientific team took the Enkanini and Delft participants on a tour of their lab and the SUN microbiology department, to involve them more deeply in their research and open up another space for questions and answers.

Gill argues that the value of participatory methods such as body mapping lies in their accessibility. During her presentation, Gill explained how the visual nature of these methods enables non-researcher participants to articulate their experiences and convey their opinions more easily than through the use of words alone. Gill also described how PVM outputs can be disseminated to, and understood by, a wide range of audiences. However, she also cautioned that working with PVM involves a large degree of openness and sharing. So that the researchers could understand the vulnerability that comes with telling personal stories, the SLF team asked them to create “hand maps” to outline their individual journeys into microbiology research. The scientists shared their personalized hand maps with the BLH community participants at the beginning of the knowledge exchange workshops, as a way of introducing themselves. Gill described how this process showed the scientists to be approachable people who are emotionally connected to their work, and how it provided a springboard for more engaged interactions.

Reflection

20 attendees at the 2018 Wellcome International Engagement Workshop discussed PVM in an open space exercise where a number of important questions were raised. Some questions related to practical aspects of PVM, such as the key practicalities to be thought through when making a decision about which method to follow. Other questions highlighted the possible ethical difficulties that may arise when using visual and storytelling approaches, e.g. as a facilitator, how do you deal with personal, sometimes difficult experiences that may surface through the use of these methods? Is it ethical to create visuals of very sick people? As the outputs of any PVM process are likely to be quite personal, what happens if a researcher misinterprets a visual i.e. presents it to other groups in the wrong way? How can complex medical health messages be conveyed in such a creative context? What happens if the needs or concerns that are uncovered by this process are beyond the reach of the researchers to address? How can it be ensured that other partners in a PVM process can respond so that exposed vulnerabilities are not left unhealed?

These are important questions to ask when deciding whether PVMs are correct for the context and issue, but the benefits of the approach are also many fold. Working with visual methods can be highly therapeutic for participants; they can allow them to voice themselves in ways they have not been able to before, and to convey complicated and personal experiences to those with power to change their circumstances.

Gill has created an email list for those interested to find out more about PVM; click here to email Gill if you're interested in joining.

Gill is currently working in partnership with Dr. Mary Chambers at OUCRU in Vietnam to develop an e-learning course for Mesh on the practice and ethics of working with PVM for public engagement in health and health science research.

Bucket Loads of Health was fully supported by the Wellcome Public Engagement Fund,

Dr. Gill Black is Director at the Sustainable Livelihoods Foundation (SLF), an independent research and engagement organization based in Cape Town, South Africa.

Download Gill’s slides here.

---

The content on this page forms part of the online report for the 2018 International Engagement Workshop “Taking it to the Next Level: How can we generate leadership and develop practice in engagement?". To learn more about the workshop, access the rest of the report and browse the video presentations, discussion summaries, and tools, visit the workshop page.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Please Sign in (or Register) to view further.