doi.org/10.48060/tghn.131

While planning my graduate project, i felt that it would be important that my work contributed to building the capacity of children both in science and health. In addition to my background in Medical Laboratory Sciences, I worked as a trainee in a research institute and regularly visited research institutes in my area where I talked to researchers in my field. At times I was frustrated that researchers' work often feels far removed from the community. I envision a world where researchers are able to share their knowledge and valuable experience with the community, particularly children.

With this vision, I decided to involve primary school students during the data collection process in my graduate project to ensure a community-driven approach. As far as I'm aware, this is the first time to engage primary school students as citizen scientists in Sudan. The context of my research was the Dengue outbreak in Khartoum State.

With this vision, I decided to involve primary school students during the data collection process in my graduate project to ensure a community-driven approach. As far as I'm aware, this is the first time to engage primary school students as citizen scientists in Sudan. The context of my research was the Dengue outbreak in Khartoum State.

I divided my plan into two phases: a community-based phase; and a laboratory-based phase to determine the presence of dengue virus which, unfortunately, I couldn't complete due to the ongoing war. During the community-based phase, I worked with 400 students (aged 9 - 11 years old) in three schools in different localities in Khartoum state—Khartoum, Omdurman, and Bahri.The objective was not only to gather data but also to inspire and empower the students to take an active role in addressing NTDs and think as a real researcher. The following activities were conducted at each school:

Day 1:

Day 1:

- Administering a Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices (KAP) questionnaire on Dengue at the beginning of the day to assess the students' baseline understanding.

- Delivering an engaging one-hour presentation, utilising informative posters to raise awareness and educate the students about NTDs and mosquito surveillance.

- Demonstrating the proper techniques for mosquito collection using the provided tools, ensuring that the students were equipped with the necessary skills.

- Distributing the collection tools to the students, fostering a sense of ownership and engagement.

Day 2:

- Gathering the collected samples from the students.

- Conducting a questionnaire focused on identifying potential mosquito breeding sites, encouraging critical thinking and problem-solving among the students.

- Conducting brief interviews with a selected group of students to evaluate their overall experience, allowing them to reflect on their involvement and provide valuable feedback.

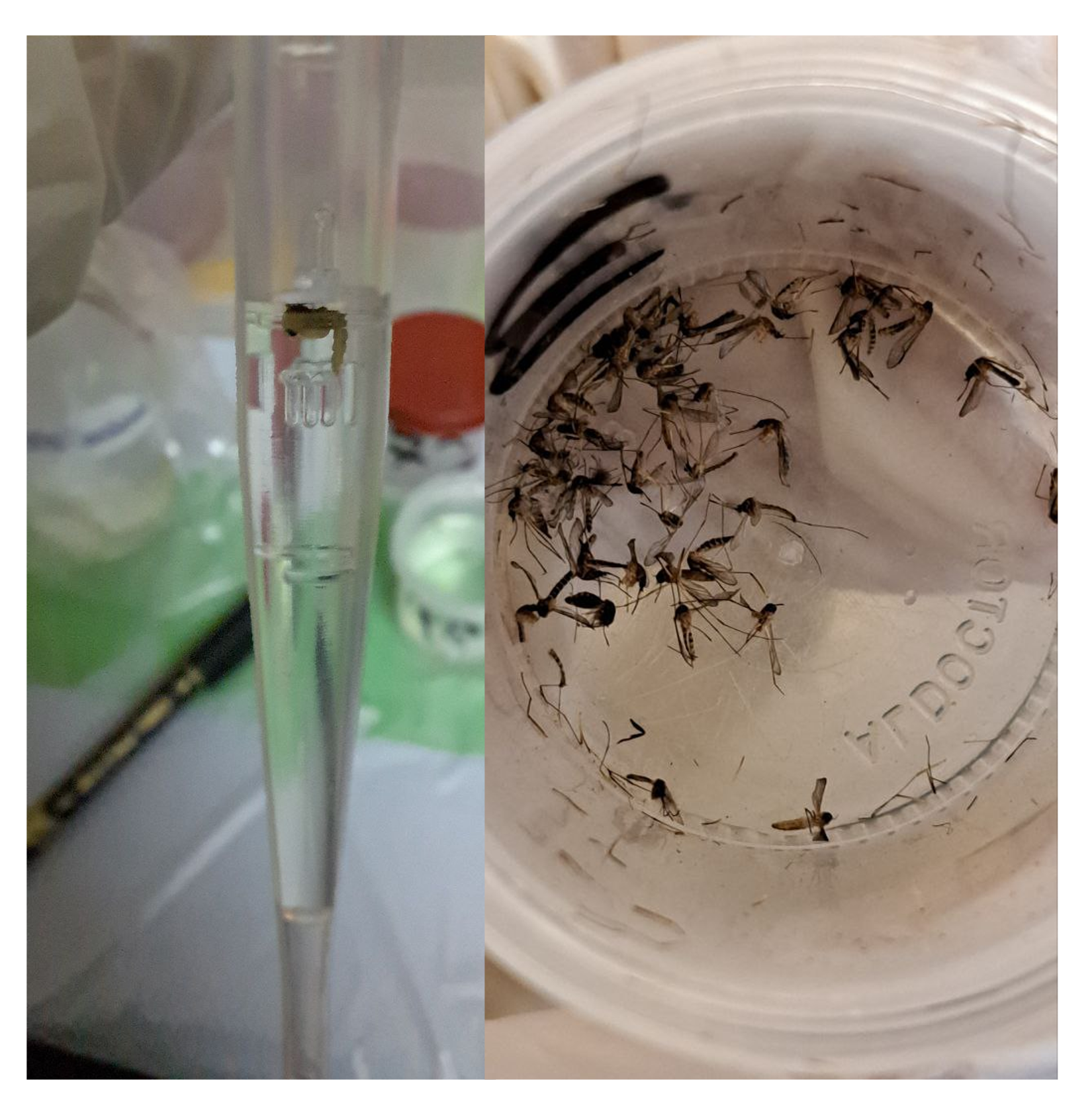

Choosing appropriate collection tools for students aged 9 to 11 presented a challenge. However, with the guidance of my brilliant supervisor Dr. Arwa Elaagip, we successfully addressed this issue. Each student was provided with the following items:

- Clean urine containers for mosquito collection.

- Pasteur pipettes or nylon strainers (Some students were very excited to use the Pasteur pipette, although it proved a little challenging for them).

Fifteen percent of the students achieved successful collections. All mosquito stages (eggs, larvae, pupae, adults ) were present in the containers. I was surprised that 2 of the students were able to correctly identify and collect the sticky black aedes eggs. However, several factors influenced these results:

- The limited duration of the training session, which lasted only one hour.

- For most of the students, this was their first experience with mosquito collection, requiring them to adapt quickly.

- Time constraints allowed for only one day of sample collection, which affected the overall quantity of samples obtained.

During the interviews, all the students expressed their willingness to participate again! One of their valuable recommendations was to have microscopes in their schools, allowing them to observe mosquitoes themselves. Inspired by this suggestion, I propose establishing connections between higher education institutions, research institutes and primary schools, creating programmes that facilitate educational visits to university laboratories and research institutes. This would provide children with the opportunity to explore the world of scientific research and ignite their passion for discovery.

During the interviews, all the students expressed their willingness to participate again! One of their valuable recommendations was to have microscopes in their schools, allowing them to observe mosquitoes themselves. Inspired by this suggestion, I propose establishing connections between higher education institutions, research institutes and primary schools, creating programmes that facilitate educational visits to university laboratories and research institutes. This would provide children with the opportunity to explore the world of scientific research and ignite their passion for discovery.

With minimal modifications, this model could be readily implemented in Sudan and worldwide. I am genuinely eager to offer my assistance to support its implementation. Drawing from my own experiences and insights gained throughout this project, I am committed to working alongside local communities, educators, and stakeholders to ensure its success.

Please Sign in (or Register) to view further.