This case study is about a proposed programme of work on evaluation of the various engagement activities (public and community) that are undertaken at the KEMRI-Wellcome Trust Research Programme (KWTRP). Engagement at KWTRP takes two main approaches;

- As programme-wide -stand-alone - pieces of work aimed at creating mutual understanding and respect between researchers, communities/public and other key stakeholders about things that matter most to them in research (e.g. social norms, science and research etc).

- Activities embedded within specific studies to create awareness and support of studies and strength the ethics of the study (e.g. ensure consent forms and process are appropriate, study activities respect the norms of the community etc.)

The evaluation will include process, outcome and impact studies and follow an action research design, iteratively feeding into the engagement activities. A variety of methods (qualitative, quantitative, participatory approaches) will be used to understand the effect and impact of the engagement activities on various outcomes – and the extent to which the engagement goals and objectives are being achieved. We will draw on our experiences of undertaking and evaluating community engagement at the Programme (KWTRP), recognising that all the key elements of community engagement - including goals of engagement, defining communities, and forms of representation - are highly complex and that evaluations need to take account of these. We think that existing evaluation frameworks, such as Realist Evaluation, Theory of Change, Outcome Mapping etc. might be useful in unpacking these complexities.

The below summarises the discussion between the presenter, discussant and the rest of the room about the case study.

The Engagement Interventions

This case study spans a broad range of activities undertaken by KEMRI and endeavours to summarise these on a programme-wide level. However, there is so much activity in the programme that in doing so the overarching goals are at risk of being lost.

Delivering interventions in a busy environment

When findings are being discussed, there was a question about which ‘intervention’ they relate to: the goals, the study, the programmes, the individual activities? The team clarified that the “intervention” in this case is the CE activities themselves. It was also suggested that a description of what it is that makes a discrete set of activities into an intervention could be a paper in itself.

An issue that many could relate to was how you evaluate your intervention when it is part of an ecosystem of interventions in a community. How do you know that other activities/interventions are not responsible for the results/effects you see? In essence, this is why we cannot definitively claim causality in our evaluation of engagement but need to make a plausible case for their influence.

The Evaluation Methods

Duality of evaluation methods

How do we reconcile the fact that the qualitative studies used to evaluate the engagement interventions might themselves be engagement and have their own influence on outcomes/results?

For example, does a Focus Group Discussion (FGD) – one of the main methods for gathering qualitative data for evaluation in this case – count as an engagement activity? Some in the room argued it was not, since in a FGD you are purely seeking information, it is akin to an interview, and there is no two-way flow of understanding or knowledge. Others argued that FGDs allow for negotiation of responsibility so are not dissimilar from engagement, and that any interaction with the community could be termed engagement.

Whether the evaluation method could be classed as an engagement intervention seemed to depend on the depth of engagement and how engagement was being defined. Focus groups might amount to different things in different contexts, and whether they are engagement or research is down to the manner in which they are conducted and the approach on the part of the researcher. There is a need for coherent language and clear definitions in each case. To broadly stamp focus groups as engagement may also mislead individuals starting out in engagement as to what engagement is and what constitutes it.

Surveys in a low literacy community

One of the other means of gathering data for the evaluation case study that was presented was through surveys. It was queried as to why this method was chosen given the low literacy in the community. The response was that evaluation had sought to combine both qualitative and quantitative elements in a complementary fashion; to gather insights on issues that were important to people, but also to gauge how widespread different themes and opinions were. It was not enough to only focus on qualitative data, as it would not be possible to find out how widespread an issue is. It was also, in part, due to the fact that the evaluation needed to speak to people working in different scientific disciplines, and be perceived as robust by those from a quantitative/positivist background.

Evaluation Approach

Practical versus conceptual reflections

It was noted that this work does not seem to give an account of middle range mechanisms of what has worked in engagement practice and the particular mix of activities and contextual factors that have made a difference. Detailing the mechanisms would be valuable for teasing out specifically what has worked to complement the overall conceptual picture. Perhaps this can be done by selecting some activities that have failed and others that have been a success and deconstructing why and how in each case.

Evaluation Goals

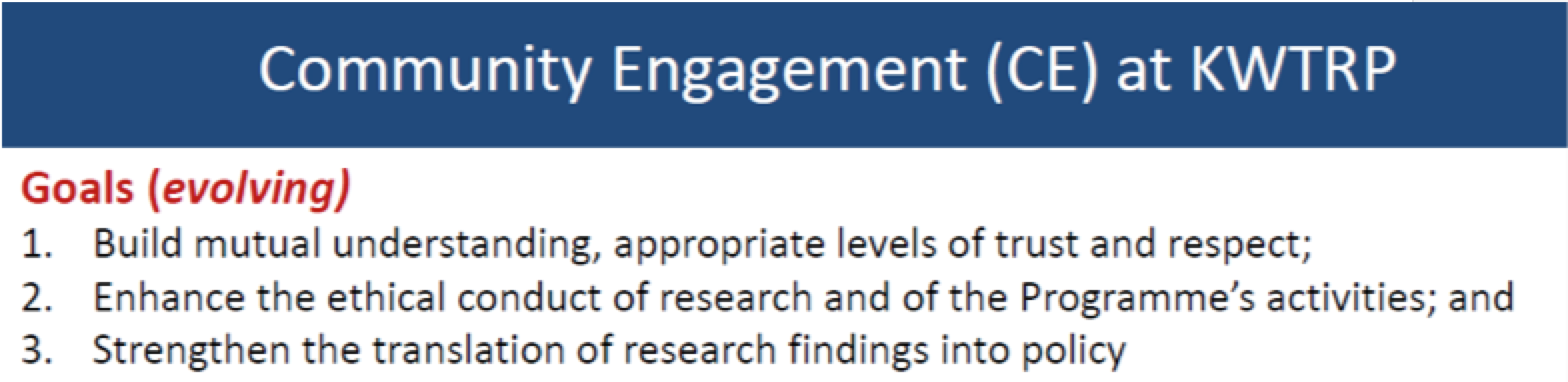

There was discussion of the importance of specifying goals clearly and concisely and the challenges of doing this. Also, the value of highlighting the overall goals of the programme and linking any learning back to these, even when discussing the evaluation of individual activities was pointed out.

In the example below, how did the use of the word “mutual” add to the meaning of the goal or was it superfluous? Superfluous words that do not add to the overall meaning and clarity of the goals are to be avoided to ensure goals are as concise and clear as possible.

The team responded that “mutual” was added as a response to the deficit model of engagement and to stress the importance of two-way engagement. So, in this case, specifying in this way adds to the intended meaning of the goal. So, it added to the meaning and the specificity of the goal. It was noted that it is important to make sure engagement goals are clearly specified.

Unpicking and justifying the use of the words used to describe a goal can be a valuable exercise. The term “understanding” was also unpicked in this case as it is a word with many interpretations: What does it mean and to whom? Do we mean the understanding of the science? Or the understanding of community perceptions of research? Or all of these?

Suggestions for writing up the Case Study

There was a discussion of how to convey both the individual engagement components and their sum in a large programme like KEMRI-WT, where so many activities and strands of engagement are brought together in one place.

Sassy Molyneux surmised:

”We have heard here more on how, and if, we should proceed with the idea presented of an overview commentary, but also that you could take strands of all the learning and write other commentaries that go into new levels of depth and add a great deal of richness”.

Thinking about the programme on a macro and micro scale in parallel is not an easy task, nor is how to present, or publish, the learning from both angles in a coherent way.

Some suggestions were:

- A high-level summary of programme-wide activity

- A portfolio of strong papers (a good number of peer-reviewed papers have already been published)

- Pulling out threads from across the individual activities (specific approaches; contexts; disease areas) and summarising those in individual commentaries

- Creating a commentary piece around the three goals KEMRI set out with threads back to the individual papers on individual activities.

Getting a comprehensive picture of a programme this rich is a challenge, more so given the narrow way that academic disciplines communicate (e.g. journal articles with a tight word limit). Discussion also highlighted the real challenge in determining who the evaluation is for, and therefore which perceptions/reflections are seen as most useful. Stakeholders who might benefit from evaluation of these interventions include implementers of engagement, communities, study PIs, funders, and all will benefit from different reflections and different means of communicating the findings. Some participants felt a responsibility not only to capture at an academic level but to simplify and define the messages of experts in the field for those establishing programmes, and those who may be new to engagement.

This case study was based on a presentation delivered at the Mesh Evaluating Community Engagement Workshop 2017. Other examples from the workshop are available here.

This resource resulted from the March 2017 Mesh Evaluation workshop. For more information and links to other resources that emerged from the workshop (which will be built upon over time) visit the workshop page.

For a comprehensive summary of Mesh's evaluation resources, and to learn how to navigate them, visit theMesh evaluation page

This work, unless stated otherwise, is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

Please Sign in (or Register) to view further.