Stigma, discrimination and social exclusion relating to HIV and substance abuse are major obstacles to health seeking, recovery and meaningful community participation in Zimbabwe, but they are not well understood.

Clement Nhunzvi is a Zimbabwean psychosocial occupational therapy lecturer and mental health researcher, based at the University of Zimbabwe. He is an AMARI PhD candidate at the University of Cape Town. This engagement project was supported by the DELTAS Africa Community and Public Engagement (CPE) Seed Fund.

Engaging communities on substance abuse and HIV through creative arts in Mufakose, Harare, Zimbabwe

My PhD study explored the interplay of substance abuse, HIV, stigma and social exclusion among young adults in the most high-density suburbs in Harare, Zimbabwe.

Substance abuse and HIV are prevalent conditions amongst young people in Zimbabwe. Lack of understanding and myths around HIV and its link to substance abuse largely drive the stigma, discrimination and social exclusion associated with these conditions. These factors are major obstacles to those affected accessing health support and participating in their communities.

To tackle these issues, there is a need to engage the community to raise awareness, by starting critical conversations using local knowledge systems.

In this project, we used a creative arts competition to raise awareness, generate insight and start discussion about fighting stigma and promoting social inclusion, primarily by engaging school children in the community, to optimise impact on knowledge, attitude and behaviour change. Some in this cohort were already afflicted with substance abuse and/or HIV. We tasked learners to produce creative art pieces using poetry, drawings and music.

Stakeholder engagement

We invited a variety of stakeholders from Mufakose (suburb in Harare, Zimbabwe) to a planning meeting, to create support, participation and buy-in from the community through stakeholder engagement. These included high school pupils, religious organisations, community support programmes and people afflicted with HIV and substance abuse, who had been participants in my PhD research. We also engaged critical Mufakose community groups, including the Community Social Services Department for the City of Harare.

Based on the input of these stakeholders, we designed and published a call for submissions, inviting young people to submit poetry, artwork and musical pieces with a social inclusion or anti-stigma message, to enter the competition. We distributed posters in churches, schools, shopping centres, and organisations who run HIV- or substance abuse-related programmes. Media outlets helped promote the effort to encourage a wide number of young people to join.

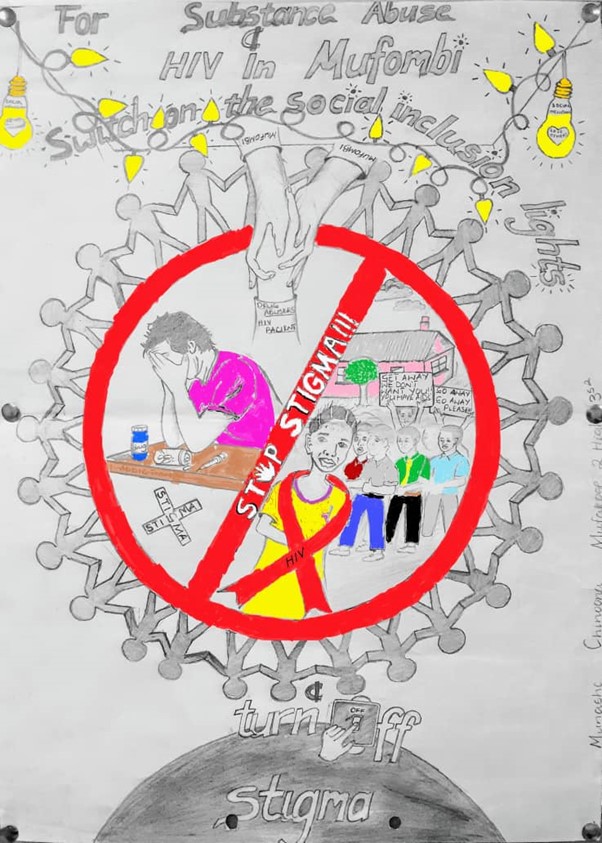

Call for entries displayed in the community and the winning entry in the visual artwork category

After the call was out, we held engagement events where I presented the CPE idea stimulating dialogue and conversations with the youths to tap into their imagination and creativity. Furthermore, we had a project assistant resident in the community to encourage young people to participate, collect entries and was readily available for support and to respond to any queries.

Community arts competition

We recruited and trained a team of ten public engagement judges from various health, education, religious and creative arts backgrounds. Some were individuals in recovery and living with HIV. Ninety-two entries were received in the preliminary competitive round, from which, thirty were selected to advance to the finals. Finalists were chosen based on how effectively their artwork portrayed messages of social inclusion and anti-stigma against HIV and substance abuse. The preparations for the grand final also served as a training ground for mentorship and coaching of the finalists, and refinement of the art works. As a result, all the artwork presented in the finals had a clear and refined anti-stigma and pro-social inclusion message for HIV and substance abuse.

Contentants reciting their poetry pieces

The final of the arts competition was attended by more than 300 invited guests, representative of the Mufakose community. Finalists presented their visual art pieces and performed poetry and music to guests. The Member of Parliament for Mufakose constituency was named Guest of Honour, cultivating policy maker engagement. Also invited were national journalists and government media outlets to help share the message of the event. These constituencies established the foundation for critical conversations on anti-stigma and social inclusion for those afflicted with HIV and substance abuse at the grassroots, policy and legislative levels.

Some of the winners with the guests of honour and Clement, the audience enjoying proceedings

Since the event, we have maintained visibility through branded CPE material, facilitating focus group discussions and evaluating the impact of the project.

Lessons and reflections on community engagement (CPE)

I had previously believed that non-expert members of the community were insufficiently knowledgeable to engage meaningfully with scientific research, imagining them limited to the role of passive consumers. I also regarded CPE as peripheral to the research process. But our experience in this work educated us about the potential for the community to be active and empowered contributors to research through well-planned and culturally relevant CPE. Effective CPE must start with generating socially relevant research questions which translate into impactful and sustainable solutions with community ownership and in which all stakeholders are equal partners.

CPE has transformed my research career: I now consider it to be a primary and integral component of holistic research, research evidence uptake and general evidence-based practice. I also plan to teach the concept to university students.

Our CPE creative arts competition appeared to have lasting effects on changing community attitude and behaviour. For example, some of the participants and their schools have now established arts clubs to promote social inclusion messaging. Branded t-shirts distributed through the project seem to have maintained an enduring presence and help to stimulate conversation: one participant noted that when they wore their t-shirt, people ask them what “social inclusion” means.

Impact

This project used novel engagement strategies which sought to challenge the traditional power imbalance in research which places the researcher as uniquely knowledgeable and community as passive subjects. We drew on strategies that value people as knowledgeable thinkers and doers, bringing out their voice and sense of ownership.

The project went an additional step in the use of competitive creative art. Some participants and stakeholders have expressed the hope that the competitions will continue to be held in the future, and potentially be replicated in other communities. One idea is to scale to a national arts competition to seed critical conversations on social inclusion nationally. Videography and recording of the final event allows for additional dissemination of the social inclusion message and potentially sets the stage to scale up.

The Ministry of Health taskforce to fight stigma associated with the COVID-19 pandemic invited me to contribute to their work based on this project.

Acknowledgements:

Our success in the CPE project is attributed to the dedication and hard work of the CPE team:

Edwin Mavindidze (Project Manager), an occupational therapist, clinical coordinator and researcher at the University of Zimbabwe occupational therapy program.

Davison Samanyada (Project assistant), a psychosocial occupational therapist at Ingutsheni Central Hospital, Ministry of Health and Child Care.

Photography by iTAP Media, Zimbabwe

This report is part of the DELTAS Africa CPE Seed Fund Programme Hub

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

Please Sign in (or Register) to view further.